From a recent piece by Michael Hudson (h/t Leo Kolivakis), economist and author of ‘Trade, Development and Foreign Debt’:

Bad economic content starts with bad methodology. Ever since John Stuart Mill in the 1840s, economics has been described as a deductive discipline of axiomatic assumptions. Nobel Prize winners from Paul Samuelson to Bill Vickery have described the criterion for economic excellence to be the consistency of its assumptions, not their realism. Typical of this approach is Nobel Prizewinner Paul Samuelson's conclusion in his famous 1939 article on "The Gains from International Trade":

“In pointing out the consequences of a set of abstract assumptions, one need not be committed unduly as to the relation between reality and these assumptions.”

This attitude did not deter him from drawing policy conclusions affecting the material world in which real people live. These conclusions are diametrically opposed to the empirically successful protectionism by which Britain, the United States and Germany rose to industrial supremacy.

Typical of this now widespread attitude is the textbook Microeconomics by William Vickery, winner of the 1997 Nobel Economics Prize:

Economic theory proper, indeed, is nothing more than a system of logical relations between certain sets of assumptions and the conclusions derived from them ...

“The validity of a theory proper does not depend on the correspondence or lack of it between the assumptions of the theory or its conclusions and observations in the real world. A theory as an internally consistent system is valid if the conclusions follow logically from its premises, and the fact that neither the premises nor the conclusions correspond to reality may show that the theory is not very useful, but does not invalidate it. In any pure theory, all propositions are essentially tautological, in the sense that the results are implicit in the assumptions made.”

Such disdain for empirical verification is not found in the physical sciences. Its popularity in the social sciences is sponsored by vested interests. There is always self-interest behind methodological madness.

That is because success requires heavy subsidies from special interests who benefit from an erroneous, misleading or deceptive economic logic. Why promote unrealistic abstractions, after all, if not to distract attention from reforms aimed at creating rules that oblige people actually to earn their income rather than simply extracting it from the rest of the economy?

Essentially, Michael is highlighting statements from some of the pioneers of modern economics in which they assert that the quality of an economic theory is independent of the theory’s ability to describe reality. Instead they suggest that economic theory is valid if it is supported by a series of logical constructs that begin with sound premises.

The economics profession has thus denounced its own usefulness, and relegated itself to the same epistemological bucket as astrology, voodoo and tarot card reading.

Hudson goes on to attribute the ubiquitous acceptance of modern ecnomics as sound 'science' to the special interests who stand to benefit from a perpetuation of the status quo.

Investors and policy-makers take note. Forewarned is forearmed.

Monday, December 21, 2009

Wednesday, December 9, 2009

Quantifying the Debt Drag

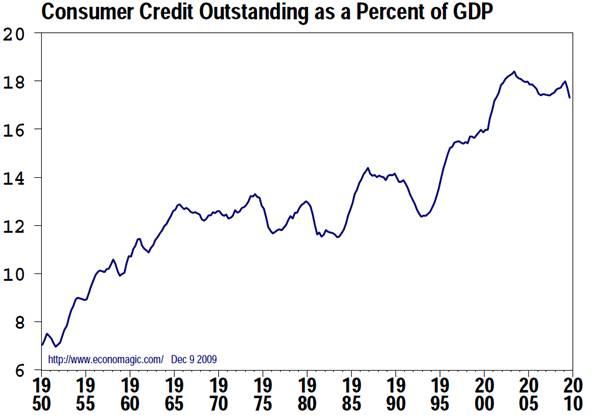

Most economists and analysts do a poor job of capturing the juxtaposition between normal cyclical recovery expectations and long-term headwinds from structural consumer over-indebtedness. Those who argue for a perpetuation of the consumer credit cycle that began post WWII and accelerated exponentially starting in 1982, with a steepening in 1994, must implicitly believe that household debt can grow to the sky.

If instead we acknowledge that households have accumulated new debt equal to 50% of rolling GDP since 1980 (chart below), thereby doubling aggregate household debt outstanding to ~102%, this implies a 2.4% p.a. boost to aggregate consumer spending over that time period. Assuming average consumer spending as a proportion of GDP was 65% over this horizon, this amounted to a boost of ~1.6% p.a. to U.S. GDP.

This analysis is upwardly biased by mortgage debt, which only flows through to GDP in the form of rents, new home construction and sales, and consumption funded by 2nd mortgages or home equity lines of credit. If we just take the increase in consumer credit (revolving and non-revolving) since 1980 (chart below), which has increased from 12.93% of GDP to 17.988% of GDP, our analysis yields a boost of 1.15% p.a. as a result of this new consumer debt. With consumer spending at 65% of GDP this would have resulted in a boost of 0.75% p.a. from unsecured lines of credit, credit card debt, and car loans alone.

It is difficult to know to what degree mortgages to purchase existing homes biased the first analysis higher, or to what degree not accounting for home equity lines of credit and second mortgages biased the second analysis lower. I think it is safe to say, however, that the annual boost to U.S. GDP from the expansion in consumer debt is between 1% and 1.25% per annum between 1980 and 2009.

Importantly, if consumer debt somehow remains constant at current nosebleed levels going forward, U.S. GDP will grow at a rate 1% - 1.25% below average growth rates since 1980. If however consumers pay-down debt at the same pace that they accumulated it from 1980 - 2008, GDP growth will drop by a further 1% - 1.25%. This would then shave a total of 2% - 2.5% from GDP growth potential, which puts likely growth rates for U.S. GDP between 1% and 2% p.a. for the foreseeable future, barring the creation of another consumer credit cycle.

Interestingly, Japanese GDP growth averaged 1.9% during its 'Lost Decade' from 1990 - 2000 after posting 10+ years of 3 - 4% growth leading up to the Nikkei's 1989 peak. Despite aggressive policies by the BOJ to bring rates to zero and a massive buildup in Japanese government debt to offset corporate and household balance sheet rebuilding, Japanese GDP was exceedingly volatile through the 1990s and share prices dropped by 65% over the decade. Of course, they are almost 75% below their 1989 peak today.

Given this anemic consumption scenario, and the Japanese template for a debt deflation scenario, investors should be asking to what degree the market is discounting a long period of slower economic growth. With consumers retrenching, boomers retiring, and government indebtedness likely to necessitate higher corporate and personal taxes in the future, is it likely that stock market valuations will continue to hold at 1980 - 2008 levels relative to the size of the economy? Or is it possible that they may revert to levels that dominated for most of the last century.

Importantly, if consumer debt somehow remains constant at current nosebleed levels going forward, U.S. GDP will grow at a rate 1% - 1.25% below average growth rates since 1980. If however consumers pay-down debt at the same pace that they accumulated it from 1980 - 2008, GDP growth will drop by a further 1% - 1.25%. This would then shave a total of 2% - 2.5% from GDP growth potential, which puts likely growth rates for U.S. GDP between 1% and 2% p.a. for the foreseeable future, barring the creation of another consumer credit cycle.

Interestingly, Japanese GDP growth averaged 1.9% during its 'Lost Decade' from 1990 - 2000 after posting 10+ years of 3 - 4% growth leading up to the Nikkei's 1989 peak. Despite aggressive policies by the BOJ to bring rates to zero and a massive buildup in Japanese government debt to offset corporate and household balance sheet rebuilding, Japanese GDP was exceedingly volatile through the 1990s and share prices dropped by 65% over the decade. Of course, they are almost 75% below their 1989 peak today.

Given this anemic consumption scenario, and the Japanese template for a debt deflation scenario, investors should be asking to what degree the market is discounting a long period of slower economic growth. With consumers retrenching, boomers retiring, and government indebtedness likely to necessitate higher corporate and personal taxes in the future, is it likely that stock market valuations will continue to hold at 1980 - 2008 levels relative to the size of the economy? Or is it possible that they may revert to levels that dominated for most of the last century.

Chart: Ratio of U.S. Stock Market Capitalization to U.S. GDP

Source: Ned Davis Research Tuesday, December 1, 2009

Hussman: We face two possible states of the world.

John Hussman manages the eponymous Hussman Funds. Hussman was among the few who both forecast the 2008/2009 credit crisis, and also had the fortitude to position his clients' defensively in advance. Returns this year have lagged global stocks, but Hussman is largely unrepentant. Like us, he lacks faith in the sustainability of the current rally, and rails against the unconstitutional actions of the Fed in supporting the bondholders of egregiously mismanaged banks.

Dr. Hussman writes a weekly column at his web site, which I strongly encourage everyone to read. This is his latest piece.

November 30, 2009

Dr. Hussman writes a weekly column at his web site, which I strongly encourage everyone to read. This is his latest piece.

November 30, 2009

Reckless Myopia

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

All rights reserved and actively enforced.

John P. Hussman, Ph.D.

All rights reserved and actively enforced.

I was wrong.

Not about the implosion of the credit markets, which I urgently warned about in 2007 and early 2008. Not about the recession, which we shifted to anticipating in November 2007. Not about the plunge in the stock market, which erased the entire 2002-2007 market gain, which was no surprise. Not about the “ebb and flow” of short-term data, which I frequently noted could produce a powerful (though perhaps abruptly terminated) market advance even in the face of dangerous longer-term cross-currents. I expect not even about the “surprising” second wave of credit distress that we can expect as we move into 2010.

From a long-term perspective, my record is very comfortable. But clearly, I was wrong about the extent to which Wall Street would respond to the ebb-and-flow in the economic data – particularly the obvious and temporary lull in the mortgage reset schedule between March and November 2009 – and drive stocks to the point where they are not only overvalued again, but strikingly dependent on a sustained economic recovery and the achievement and maintenance of record profit margins in the years ahead.

I should have assumed that Wall Street's tendency toward reckless myopia – ingrained over the past decade – would return at the first sign of even temporary stability. The eagerness of investors to chase prevailing trends, and their unwillingness to concern themselves with predictable longer-term risks, drove a successive series of speculative advances and crashes during the past decade – the dot-com bubble, the tech bubble, the mortgage bubble, the private-equity bubble, and the commodities bubble.

And here we are again.

We face two possible states of the world. One is a world in which our economic problems are largely solved, profits are on the mend, and things will soon be back to normal, except for a lot of unemployed people whose fate is, let's face it, of no concern to Wall Street. The other is a world that has enjoyed a brief intermission prior to a terrific second act in which an even larger share of credit losses will be taken, and in which the range of policy choices will be more restricted because we've already issued more government liabilities than a banana republic, and will steeply debase our currency if we do it again. It is not at all clear that the recent data have removed any uncertainty as to which world we are in.

Taking the weighted average outcome for the two states of the world still produces a poor average return/risk tradeoff. Taking the weighted average investment position for the two states of the world is somewhat more constructive. As I noted several weeks ago, I have adapted our weightings accordingly. As a result, we have been trading around a modest positive net exposure, increasing it slightly on market weakness, and clipping it on strength, as is our discipline. Currently, the Strategic Growth Fund has a net exposure to market fluctuations of less than 10%, but enough “curvature” (through index options) that our exposure to market risk will automatically become more muted on market weakness and more positive on market advances, allowing us to buy weakness and sell strength without material concern about the (increasing) risk of a market collapse.

There is no chance, even in hindsight (“could have, would have, should have” stuff) that I would have responded to the existing evidence in recent months with more than a moderate exposure to market risk during some portion of the advance since March. But our year-to-date returns might now be into a second digit had I recognized that investors have learned utterly nothing from the bubbles and collapses of the past decade. That recognition might have encouraged a greater weight on trend-following measures versus fundamentals, valuations, price-volume sponsorship, and other factors.

Still, our stock selections continue to perform well relative to the market, our risks remain well-managed through a substantial (though not full) hedge, and our investment approach has nicely outperformed the S&P 500 over complete market cycles, with substantially less downside risk than a passive investment approach. We have implemented some modest changes to improve our potential to benefit from (even ill-advised) speculative runs, but we've done fine nonetheless, and we can sleep nights.

Whether or not I have focused too much on probable “second-wave” credit risks is something we will find out in the quarters ahead – my record of economic analysis is strong enough that a “miss” on that front would be an outlier. What I do think is that over the past decade, investors (including people who hold themselves out as investment professionals) have become far more susceptible to reckless myopia than I would have liked to believe. They have become speculators up to the point of disaster.

Frankly, I've come to believe that the markets are no longer reliable or sound discounting mechanisms. The repeated cycle of bubbles and predictable crashes over the recent decade makes that clear. Rather, investors appear to respond to emerging risks no more than about three months ahead of time. Worse, far too many analysts and strategists appear to discount the future only in the most pedestrian way, by taking year-ahead earnings estimates at face value, and mindlessly applying some arbitrary and historically inconsistent multiple to them.

This is utterly different from true discounting – which does not rely on multiples, but instead carefully traces out the likely path of future revenues, profit margins, cash flows and earnings over time, and explicitly discounts expected payouts and probable terminal values back at an appropriate rate of return. That's what we actually do here. Talking in terms of multiples can make the process easier to explain, and can be a reasonable approach to the market as a whole if earnings are normalized properly, but ultimately, an investment security is a claim to a long-term stream of cash flows. It is not simply a blind multiple to the latest analyst estimate.

Fortunately, the evidence suggests that the long-term returns to a careful discounting approach tend to be strong even if investors repeatedly behave in speculative and short-sighted ways. This is because long-term returns are fully determined by the stream of cash flows actually received by investors over time, and because inappropriate valuations ultimately tend to mean-revert. In the face of speculative noise, the long-term returns from a proper discounting approach may not capture as much speculative return as might be possible, but over time, many of those speculative swings tend to wash out anyway.

In part, the market's increasing propensity toward speculation reflects the increasing lack of fiscal and monetary discipline from our leaders. Policy makers who seek quick fixes and could care less about long-term consequences undoubtedly encourage investors to embrace the same value system. Paul Volcker was the last Fed Chairman to have any sense that discipline and the acceptance of temporary discomfort was good for the nation.

Our current Fed Chairman's voice literally quivers in response to the phrase “bank failure,” even though in the present context, a bank failure implies none of the disorganized outcomes that characterized the Great Depression. It simply means that the bondholders take a loss and the remaining part of the institution survives intact as a “whole bank” entity (and can be sold or re-issued back to public ownership, less the debt to bondholders, as such). The same outcome would have been possible with Lehman had the FDIC been granted authority from Congress to take conservatorship of a non-bank financial entity.

In my estimation, there is still close to an 80% probability (Bayes' Rule) that a second market plunge and economic downturn will unfold during the coming year. This is not certainty, but the evidence that we've observed in the equity market, labor market, and credit markets to-date is simply much more consistent with the recent advance being a component of a more drawn-out and painful deleveraging cycle. Meanwhile, valuations are clearly unfavorable here, and even under the “typical post-war recovery” scenario, we are observing an increasing number of internal divergences and non-confirmations in market action.

As Gluskin Sheff chief economist David Rosenberg noted last week, “Even if the recession is over, the historical record shows that downturns induced by asset deflation and credit contraction are different than a garden-variety recession induced by Fed tightening and excessive manufacturing inventories since the former typically induce a secular shift in behavior and attitudes towards debt, asset allocation, savings, discretionary spending and homeownership. The latter fades more quickly.

“This is why people didn't figure out that it was the Great Depression until two years after the worst point in the crisis in the 1930s; and why it took decades, not months, quarters or even years, for the complete transition to the next sustainable economic expansion and bull market.

“Mortgage applications for new home purchases hit a 12-year low in the middle of November (down 22% in the past month!), fully two weeks after the Administration said it was going to not only extend but expand the program to include higher-income trade-up buyers. Once again, there is minimal demand for autos and housing, and that is partly because the market is still saturated with both of these credit-sensitive big-ticket items after an unprecedented credit and consumer bubble that went absolutely parabolic in the seven years prior to the collapse in the financial markets an asset values. We are probably not even one-third of the way through this deleveraging cycle. Tread carefully.”

Andrew Smithers, one of the few other analysts who foresaw the credit implosion and remains a credible voice now, concurred last week in an interview with my friend Kate Welling (a former Barrons' editor now at Weeden & Company): “The good news so far is that the stock market got down to pretty much fair value or even, possibly, a tickle below it, at its March bottom. But now it has gone up… we probably have a market which is, roughly, 40% overpriced. In order to assess value, it is necessary either to calculate the level at which the EPS would be if profits were neither depressed nor elevated, or to use a metric of value which does not depend on profits. The cyclically adjusted P/E (CAPE) normalizes EPS by averaging them over 10 years. It thus follows the first of those two possible methods. Using even longer time periods has advantages, particularly as EPS have been exceptionally volatile in recent years - and using longer time periods raises the current measured degree of overvaluation. The other methodology we use measures stock market value without reference to profits: the q ratio. It compares the market capitalization of companies with their net worth, also adjusted to current prices. The validity of both of these approaches can be tested and is robust under testing - and they produce results that agree. Currently, both q and CAPE are saying that the U.S. stock market is about 40% overvalued.”

In the chart below, the current data point would be about 0.4, not as extreme as we observed in 1929, 2000, or 2007 of course, but equal to or beyond what we've observed at virtually every other market peak in history. This aligns well with our own analysis, where as I've noted in recent weeks, the S&P 500 is priced to deliver one of the weakest 10-year total returns in history except for the (ultimately disappointing) period since the mid-1990's.

One of the fascinating aspects of the past few months is the lack of equilibrium thinking with respect to what happened to the trillions of dollars in government money that has been spent to defend the bondholders of mismanaged financial companies. Almost by definition, money given to corporations will show up most quickly as improvements in corporate earnings, and then slightly later, as executive compensation. A few pieces came across my desk last week, hailing the ability of the corporate sector to bounce back from the recent economic downturn even though revenues have continued to suffer and employment has been steeply cut. Why is this a surprise? Where else could the money have gone? Labor compensation? It is truly mind-numbing that a moment after a temporary surge of trillions of dollars, borrowed and tossed out of a helicopter (though to specific corporations and private beneficiaries), analysts would hail a subsequent improvement in corporate results as evidence of “resilience.”

What matters is sustainability, and unfortunately, it is clear that credit continues to collapse. Banks are contracting their loan portfolios at a record rate, according to the latest FDIC Quarterly Banking Profile. Even so, new delinquencies continue to accelerate faster than loan loss reserves. Tier 1 capital looked quite good last quarter, as one would expect from the combination of a large new issuance of bank securities, combined with an easing of accounting rules to allow “substantial discretion” with respect to credit losses. The list of problem institutions is still rising exponentially. Overall, earnings and capital ratios have enjoyed a reprieve in the past couple of quarters, but delinquencies have not, and all evidence points to an acceleration as we move into 2010.

Urgent Policy Implications

From a policy standpoint, it is effectively too late to forestall further foreclosures absent explicit losses to creditors. The best policy option now is to make sure that the second wave does not result in a debasement of the U.S. dollar. The way to do that is to require three things:

First, the FDIC should be given regulatory authority to take non-bank financials into conservatorship the way they should have been able to do with Bear Stearns and Lehman. If this authority had existed in 2008, Bear's bondholders would not now stand to get 100% of their money back, with interest, as they presently do, and Lehman's disorganized liquidation would have been completely unnecessary. As I've noted before, the problem with Lehman was not that it went bankrupt, but that it went bankrupt in a disorganized way. If the FDIC had authority over insolvent non-bank financials and bank holding companies, it could wipe out equity and an appropriate amount of bondholder capital, and sell the fully-functioning residual to an acquirer, as is typically done with failing banks, without any loss to depositors or customers.

Second, bank capital requirements should be altered to require a substantial portion of bank debt to be of a form that automatically converts to equity in the event of capital inadequacy. This would force losses onto bondholders, rather than onto taxpayers. This policy adjustment is urgent – we have perhaps a few months to get this right.

Finally, Congress should be clear that government funds will be available only to protect the interests of depositors, not bondholders. Specifically, any funds provided by the government should be contingent on the ability to exert a senior claim to bondholders in the event of subsequent bankruptcy, even if a category is created to allow those funds to be counted as “capital” for purposes of satisfying capital requirements prior to such bankruptcy. Government-provided capital should be subordinate only to depositor claims, if equity and bondholder capital ultimately proves insufficient to meet those obligations.

Since early 2008, beginning with the provision of non-recourse funding in the Bear Stearns debacle, the Federal Reserve and the Treasury have repeatedly allocated or implicitly obligated public funds to defend the bondholders of mismanaged financial companies. This has included the outright and non-recourse purchase of nearly a trillion dollars in mortgage securities that have no explicit guarantee by the U.S. government. By purchasing these securities outright (rather than through a well-defined repurchase agreement), the Fed is effectively obligating the U.S. government to either guarantee them or to absorb any future losses.

Aside from the fraction of bailout funding that was specifically allocated by Congress through legislation, these actions represent an unconstitutional breach into enumerated spending powers that are the domain of the elected members of Congress alone. The issue here is not whether the Fed should be independent from political influence. The issue is the constitutionality of the Fed's actions. The discretion that it has exerted over the past two years crosses the line into prerogatives reserved for Congress. That line needs to be clarified sooner rather than later.

Emphatically, the trillions of dollars spent over the past year were not in the interest of protecting bank depositors or the general public. They went to protect bank bondholders. Instead of taking appropriate losses on those bonds (which financed reckless mortgage lending), those bonds are happily priced near their face value, for the benefit of private individuals, thanks to an equivalent issuance of U.S. Treasury debt. But that's not enough. Outside of a very narrow set of institutions that are subject to compensation limits, just watch how much of the public's money – which benefitted several major investment banks following a very direct route – gets allocated to Wall Street bonuses in the next few weeks.

Market Climate

As of last week, the Market Climate for stocks remained characterized by unfavorable valuations and mixed market action. The market remains significantly overbought on an intermediate-term basis, and we've seen increasing divergences from breadth, small and mid-cap stocks, trading volume, and other internals, which have lagged the most recent advance in the S&P 500 and other cap-weighted indices.

The prospect of a debt-repayment “standstill” from Dubai prompted some weakness in foreign markets that spilled over to the U.S. on Friday. This was interesting given that David Faber reported the issue on CNBC on Wednesday, to no reaction. Importantly, the payment difficulties do not stem from oil revenues, but largely from tourism and financial activity, as those are Dubai's chief industries (Dubai is home to the tallest building and the largest man-made islands in the world, for example). From that standpoint, it is difficult to imagine much in the way of contagion as a result of Dubai's difficulties.

Whatever shock the market will get from left field is likely to come from larger financial or geopolitical risks. The market for credit default swaps bears watching, but thus far we haven't observed spikes to indicate that something major is imminent. Unfortunately, as I noted earlier, investors have earned an “F” for vigilance in recent years, so our lead time on new difficulties may be shorter than we might like.

In any event, I'm pleased with the overall behavior of our stock holdings, and I expect that we'll have plenty of opportunity to increase our exposure to market fluctuations at more appropriate valuations. Presently, we've got a small amount of exposure to market fluctuations, but not enough to cause any material difficulties if the market experiences some trouble. The largest source of day-to-day fluctuations remains the difference in performance between the stocks we hold long and the indices we use to hedge. That source of risk has also been the primary contributor to returns over the life of the Fund.

In bonds, the Market Climate was characterized last week by moderately unfavorable yield levels and generally favorable yield pressures. We saw a good example of how the market is inclined to respond to fresh credit concerns last week, with upward pressure on the U.S. dollar and U.S. Treasuries, and downward pressure on foreign currencies and commodities. While I continue to believe that the dollar faces substantial risk of further erosion in its exchange value, as well as a near doubling of the CPI over the coming decade or so (both reflecting the massive increase in U.S. government liabilities in recent years), those prospects are not likely to emerge until risk-aversion about credit default materially abates. Credit concerns typically create a spike in demand for default-free assets such as U.S. government liabilities, so even though there is a much larger float than is likely to be sustained over time without inflation as the ultimate outcome, credit concerns tend to support the value of these liabilities and hence mutes immediate inflation pressures (essentially, monetary velocity declines as these liabilities are sought as a default-free store of value).

The Strategic Total Return Fund currently has an overall duration slightly over 3 years, primarily in straight Treasuries, with a small 1% exposure to precious metals shares and about 4% of assets in utility shares.

Friday, September 11, 2009

Welcome to the Liquidity Surge

I've been trying to reconcile the apparent mixed signals in credit markets relative to stock markets in the past 2 months.

Inflation expectations implied by the 10-Year TIPS breakeven rate broke an intermediate-term downtrend on Monday, suggesting that investors are not overly concerned with deflation at the moment. However, a broken downtrend is not the same as an up-trend.

Meanwhile, rates have declined substantially all along the curve, signaling that bond market investors have no fear of inflation anywhere.2-year rates are breaking down around the world.

Stocks, copper and gold have moved to new bull market highs, with oil close behind.

The only explanation that seems to make sense is that this is the beginning of the next liquidity surge as the banks start to make use of those reserves at the Fed. They are moving out the curve (from zero duration) and driving risk capital out the risk spectrum. Even 88bps in the 2-year is better than 25 bps or less for funds on deposit at the Fed.

As the banks move into notes they will drive 2-year yields down. Investors will then move out the curve looking for yield, which will push longer maturity bond prices higher. This is the only explanation I can come up with for the coincident rally in bonds, stocks, copper and gold.

We’ll drive stock multiples back into the stratosphere, as the economy is clearly not supportive of the assumed risk premia.

Watch the TIPS BE rate (USGGBE10:IND in Bloomberg) for a signal of trend reversal. Until then, we are firing on all cylinders.

Welcome to the liquidity surge.

Inflation expectations implied by the 10-Year TIPS breakeven rate broke an intermediate-term downtrend on Monday, suggesting that investors are not overly concerned with deflation at the moment. However, a broken downtrend is not the same as an up-trend.

10-Year TIPS Breakeven Rate (Implied Inflation Expectations)

Source: Bloomberg

Global 2-Year Government Bond Yields

Source: BMO CM Research

Longer-term rates broke their intermediate-term downtrend line in August, but have broken back above their short-term downtrend. A break of 3.265% on the US Ten-Year would signal a new intermediate-term downtrend. This might give equity investors pause, but in light of the relentless, mindless bullishness currently extant, lets not hold our breath.

Ten-Year Treasury Bond Yield

Source: Stockcharts.com

streetTRACKS Gold Trust ETF

Source: Stockcharts.com

The only explanation that seems to make sense is that this is the beginning of the next liquidity surge as the banks start to make use of those reserves at the Fed. They are moving out the curve (from zero duration) and driving risk capital out the risk spectrum. Even 88bps in the 2-year is better than 25 bps or less for funds on deposit at the Fed.

Source: FRB

As the banks move into notes they will drive 2-year yields down. Investors will then move out the curve looking for yield, which will push longer maturity bond prices higher. This is the only explanation I can come up with for the coincident rally in bonds, stocks, copper and gold.

We’ll drive stock multiples back into the stratosphere, as the economy is clearly not supportive of the assumed risk premia.

Watch the TIPS BE rate (USGGBE10:IND in Bloomberg) for a signal of trend reversal. Until then, we are firing on all cylinders.

Welcome to the liquidity surge.

Friday, September 4, 2009

1930's Redux

David Rosenberg quoted from a September 1930 Wall Street Journal editorial in this morning's 'Breakfast with Dave'. With Spiritus Animus bubbling to the surface today, wise investors would be well served to keep things in perspective. The following piece should put even the most bullish data and comments in context:

August 28, 1930:

August 28, 1930:

"There’s a large amount of money on the sidelines waiting for investment opportunities; this should be felt in market when “cheerful sentiment is more firmly entrenched.” Economists point out that banks and insurance companies “never before had so much money lying idle.”September 3, 1930:

"Market has now reached [the] resistance level where it ran out of steam on July 18 (240.57) and July 28 (240.81). Breaking through this level would be considered a highly bullish signal. General confidence that this will happen based on recent market action; many leading stocks have already surpassed July highs. Further positive technicals seen in recent volume pattern (higher on rallies and lower on pullbacks), and in continued large short interest.

Some wariness based on recent good rally recovering all of drought-related break; some observers advise taking profits on at least part of long positions, to be in position to rebuy on good pullbacks.

Most economists agree business upturn is close; peak in business was reached July 1929, so depression has lasted about 14 months. “Those who have faith and confidence in the country and its ability to come back will profit by their foresight. This has also been the case over the past half century.”

Harvard Economic Society points to steady rise in bond prices as favorable for stocks. Says there is “every prospect that the [business] recovery ... will not long be delayed,” although fall period may not be strong as expected. Notes worldwide decline in business, but 1922 recovery demonstrates U.S. due to “great size, natural advantages, and diversity of conditions ... can lift itself out of depression without the stimulus of improved foreign demand.”Rosenberg concludes with the ominous, "We only know now with perfect hindsight what these pundits did not know back then — that there was another 80% of downside left in the bear market."

Thursday, September 3, 2009

Low Quality Rally

Many Advisors and fund managers have been complaining about how difficult it has been to beat their stock market benchmarks since the March 9th bottom. It turns out that, for active managers with a rigorous process for selecting the highest quality stocks, it has been quantifiably frustrating. This post will shed some light on this topic, to the delight of disciplined stock-pickers everywhere.

Over long periods (> 2 years) 'high-quality' stocks outperform 'low-quality' stocks by a substantial margin. A stock's 'quality' in this sense is defined by its relative standing among factors such as earnings growth and momentum, earnings stability, debt-to-equity, trading liquidity, return-on-equity, credit rating, analyst earnings estimate revisions, price level and price momentum, etc. However, since March 9th, an investor who stuck to a discipline of choosing only 'high-quality' stocks for portfolios would have substantially underperformed North American benchmarks.

It may seem intuitive that stocks that dropped the most during the bear market (worst momentum, smallest market cap at the bottom, lowest price at the bottom) have shown some of the greatest returns off the bottom. This intuition is faulty however, for several reasons. First, those who own the stocks that dropped the most - owned the stocks that dropped the most. Very few investors were able to time the purchase of these cataclysmic names, like Citigroup, Bank of America, and AIG so that they avoided the bloodbath before experiencing the ecstasy of rebirth. Even the bravest value investors like Bill Miller, whose Legg Mason Value Trust had one of the strongest 10-year track records of any mutual fund until late 2007, saw his fund value drop from $85 to $22, a drop of 74% (!!) before seeing his fund rebound by almost 100% since March 9th. His fund is still down over 50% from its peak.

Another reason why it makes little sense to try to buy the stocks that have dropped the most during bear markets is that these stocks usually underperform over the duration of the subsequent bull market. The 2000 - 2003 bear market is a great example. The stocks that went down the most in the bear market - JDS Uniphase, Nortel Networks, Mindspring, Cisco, etc. were very weak performers from 2003 - 2007. The strongest performers throughout the 2000 - 2003 bear market - energy, materials, and gold companies - were enormous winners during the following bull market. This is the rule, not the exception.

Myles Zyblock, Chief Institutional Strategist for RBC Capital Markets wrote the following in his September 1st note to clients:

"North American stock-specific leadership, regardless of sector membership, has been characterized by a type of constituency that most analysts refer to as “low quality”. This has been a rather unnerving shift for managers who follow a discipline that emphasizes particular attributes such as earnings quality or profitability. Many mandates have not allowed managers to enter this low-quality style box, to the detriment of relative performance. Strict adherence to a process more often than not leads to investment success, but the market can and often does move against a winning long-term strategy for brief time periods. Keep in mind that low quality cycles, even in up markets, tend to be relatively short-lived and our best guess is that there are only another 1-2 quarters of life left in this one.

One way to get a sense of what the low quality rally has been all about is to view the performance of stocks since the March low sorted by a few simple metrics that isolate the impact of quality factors including size/liquidity, valuations and profitability. Based on this methodology, it’s pretty clear that the smaller, less liquid, relatively inexpensive and more fundamentally broken companies have been the big outperformers over the past five months. " (See Table 1.)

Table 1. S&P 500 Returns Since March 9th By Decile Rank

The next chart shows the performance of North American stocks, with S&P performance on the left, and TSX performance on the right. The grey bars represent the performance of highest quality stocks in each of the four major investment styles - Momentum, Predictability, Growth, and Value - while the blue bars show the performance of the lowest quality stocks. All performance is from the March 9th bottom.

High quality U.S. stocks underperformed low-quality stocks in every category, though the outperformance in the Value category is minor. This makes sense, as at the bottom many of the low quality stocks were priced well below book value, on the assumption that many would be liquidated as non-viable businesses. Of course, without unprecedented government intervention, many of the worst performing stocks would have collapsed, and these numbers would look quite different.

In Canada, high-quality outperformed low-quality Value stocks quite substantially. Canadian Value managers have had the most prospective stock-picking environment in generations, while growth and momentum managers have dramatically underperformed.

Overall, the above charts show that rapidly declining companies with highly unpredictable financials and significant earnings contraction as of March 9th very significantly outperformed stocks with predictable financials, strong earnings growth, and which were already in positive price trends.

History shows that this dynamic is not that unusual in frequency, but that it doesn't last for very long. According to RBS research, low-quality stocks have outperformed high-quality stocks during 8 periods in the past 30 years, and this performance advantage tends to persist for about 6 to 9 months. So low quality stocks may continue to dominate for another three months or so.

To further illustrate the point of low-quality dominance, I have included two tables below describing the performance of several style models from Canada's Computerized Portfolio Management Services (CPMS). The top table shows U.S. models, and the bottom table shows Canadian models.

Each style model (Asset Value, Earnings Value, Earnings Momentum, etc.) tracks a portfolio of stocks chosen using different high-powered factors, such as earnings momentum, earnings predicability, analyst estimate revisions, price-to-book value, price momentum, etc. The 'Dangerous' model in each table tracks the performance of a portfolio of stocks which the system suggests would make good short candidates. These are the lowest quality stocks, with poor earning growth and quality, negative analyst estimate revisions, high debt levels relative to equity, etc.

Note that over the past year the 'Dangerous' models have outperformed every model except the Canadian 'Earnings Value' model. This makes sense, as the Dangerous portfolio closely approximates a low-quality value portfolio, while the 'Earnings Value' model replicates a high-quality Value portfolio.

The Momentum portfolio in Canada, and the Earnings and Price Momentum portfolios in the U.S. have demonstrated the best performance since inception (1985 and 1993 for the Canadian and U.S. models respectively) by a wide margin (see far right column). However, these models have been terrible under-performers since the beginning of this year.

Source: CPMS

Source: CPMS

Fortunately, we can be confident that the low-quality rally won't last forever. If this rally provides us with another leg up, disciplined adherents to high-quality stock picking strategies will almost certainly get their day in the sun.

The Statistics of Prediction

Given the high level of ambiguity in the economy and markets at the moment (both gold and Treasuries rallying?), I thought it might be useful to revisit the concept of forecast error. Economic forecasters, even (perhaps especially?) the top, highest paid Wall Street celebrity economists, are egregiously poor predictors of stock market levels or direction over any meaningful time frame.

Robert Prechter does an excellent job of describing the logical fallacy about economists:

From Elliott Wave Theorist, May 2009

From Elliott Wave Theorist, May 2009

"Although it has suddenly become fashionable to bash economists, I would like to point out that economists are very valuable when they stick to economics. They can explain, for example, why and individual's pursuit of self interest is beneficial to others, why prices fall when technology improves, why competition breeds cooperation, why political action is harmful, and why fiat money is destructive. Such knowledge is crucial to the survival of economies.

Economic theory pertains to economics, but not to finance and so-called macro-economics. Socionomic theory pertains to social mood and its consequences, which manifest in the fields of finance and macro-economics.

If you want someone to explain why minimum wage laws hurt the poor, talk to an economist. But if you want someone to predict the path of the stock market, talk to a socionomist.

The two fields are utterly different, yet economists don't know it.

How Correct are Economists Who Forecast Macro-Economic Trends?

The Economy is usually in expansion mode. It contracts occasionally, sometimes mildly, sometimes severely. Economists generally stay bullish on the macro-economy. In most environments, this is an excellent career tactic. The economy expands most of the time, so economists can claim they are right, say, 80 percent of the time, while missing every turn toward recession and depression.

Now, suppose a market analyst actually has some ability to warn of downturns. He detects signs of a downturn ten times, catching all four recessions that actually occur but issuing false warnings six times. He, a statistician might say, is right only about 40 percent of the time, just half as much as most economists; therefore the economist is more valuable. But these statistics are only as good as the premises behind them.

Suppose you eat at an outdoor cafe daily, but it happens that on average once every 100 days a terrorist will drive by and shoot all the customers. The economist has no tools to predict these occurrences, so he simply 'stays bullish' and tells you to continue lunching there. He's right 99 percent of the time. He is wrong 1% of the time. In that one instance, you are dead.

But the market analyst has some useful tools. he can predict probabilistically when the terrorist will attack, but his tools involve substantial error, to the point that he will have to choose on average 11 days out of 100 on which you must be absent from the cafe in order to avoid the day on which the attack will occur. This analyst is therefore wrong 10% of the time, which is ten times the error rate of the economist. But you don't die.

How can the economist be mostly right yet worthless and the analyst be mostly wrong yet invaluable? The statistics are clear - aren't they?

The true statistics, the ones that matter, are utterly different from those quoted above. When one defines the task as keeping the customer alive, the economist is 0% successful, and the analyst is 100% successful.

When consequences really matter, difference in statistical inference can be a life and death issue. In the real world, business people need timely warnings, and realize that economists miss most downturns entirely. Would you rather suffer several false alarms, or would you rather get caught in expansion mode at the wrong time and go bankrupt?

Focus on irrelevant statistics is one reason why economists have been improperly revered, and some analysts have been unfairly pilloried, during long-term bull markets. But economists' latest miss was so harmful to their clients that their reputation for forecasting isn't surviving it."The following table offers a stark example of forecaster fallibility. Every December, Barron's financial journal gathers the top analysts from Wall Street, names most investors are familiar with, and asks them to forecast the value of the S&P500 on December 31st of the following year. Granted, this is an impossible task; a probable range might be more reasonable. But more importantly, it is also useless because markets can travel an infinite variety of paths to get from A to B, and the paths are important to anyone with an active view on the markets. Regardless, these analysts were off by such a large factor that it can legitimately be claimed that they offer no predictive value, whatsoever.

Source: Bloomberg, Butler|Philbrick & Associates

Note that the average estimate of 1650 from these 12 Chief Economists was 82% above the actual closing value on December 31st.

A recent study by James Montier of Societe Generale suggests that stock strategists at Wall Street’s biggest banks -- including Citigroup Inc., MorganStanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. -- have failed to predict returns for the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index every year this decade except 2005. Their forecasts were w rong by an average of 18 percentage points, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

A recent study by James Montier of Societe Generale suggests that stock strategists at Wall Street’s biggest banks -- including Citigroup Inc., MorganStanley and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. -- have failed to predict returns for the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index every year this decade except 2005. Their forecasts were w rong by an average of 18 percentage points, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

There is a mountain of evidence supporting the view that economist forecasts are statistically no more accurate than random guesses around a long-term trend. Yet most, if not all, Advisors eagerly follow the views of their favorite economist closely, and generally adhere to their recommendations. What is the definition of 'deranged'? Repeating the same mistake over and over while expecting a different result.

Monday, August 31, 2009

Macro Indicator Summary

I am impressed with markets' resilience in the face of China's 6.7% sell-off overnight. Aside from Hong-Kong, global equity markets have shrugged-off the new Chinese bear market with a disinterested grunt. Here in Canada, banks are mostly higher on the day despite a 1.5% drop in the index, while the U.S. banking sector continues to consolidate sideways, off just 0.75% today.

4:30pm update: Volume was lower across the board, so institutions are sitting on their hands.

9:30pm update: After-hours volume pushed end-of-day numbers well above yesterday's levels, registering a 'distribution day'.

4:30pm update: Volume was lower across the board, so institutions are sitting on their hands.

9:30pm update: After-hours volume pushed end-of-day numbers well above yesterday's levels, registering a 'distribution day'.

Note: Please click on any and all charts for a larger image.

The clear losers from the China sell-off are commodities, with oil down $3 to below $70, and copper off 12 cents at 2.83. Oil is at critical support from a trend-line going back to late April (see chart of DBO below), while copper has reversed off important resistance at the 61.8% Fibonacci retracement level of $3.00 (See copper Fibs below).

DBO Oil Fund ETF

Source: Stockcharts.com

Copper Market with Fibonacci Levels

Source: Stockcharts.com

Commodity currencies, like the CAD and AUD sold off substantially earlier in the day but have since rebounded, especially against the Yen. The CAD/USD found support from its 50 day moving average slightly below 90 in the morning, and is likely to test its multi-week trend-line (currently at ~89) before finding further direction.

Canadian Dollar ETF

Source: Stockcharts.com

Canadian Dollar ETF / Japanese Yen ETF Ratio

Souce: Stockcharts.com

We monitor the Asian Dollar Index for macroeconomic strength in that region. The index has been consolidating for several weeks in a pennant formation which is likely to break up or down in the next few days. Given the ADXY's strength in the face of China's panic sell-off overnight, an upside breakout is more likely. On an upward break-out, there is resistance at the previous high (~109) which, if broken, would signal further emerging market strength, led by Asia.

Asian Dollar Index

Source: Bloomberg

Bonds are confirming the bearish story in commodities, with long-term Treasuries rallying to resistance for the second time in 2 days.

20+ Year US Treasury Bond ETF

Source: Stockcharts.com

The 10-year TIPS breakeven rate, a measure of bond traders' future inflation expectations, is testing key support today, suggesting that traders are skeptical of current commodity strength.

10-Year TIPS Breakeven Rate

Source: Bloomberg

10-year yields have also been consolidating in a pennant formation; a break of 3.25% would indicate a major change in the trend of 10-year rates, at which point equity bulls would necessarily be put on the defensive.

10-Year US Bond Yield

Source: Bloomberg

Gold continues to consolidate in its intermediate-term pennant structure forming the right shoulder of what looks like a huge inverse head and shoulders formation. This structure suggests higher prices lie ahead. However, there are two clear resistance levels that must be breached before we can celebrate gold's new up-trend. Using the GLD ETF chart, the first resistance line sits at ~$94.25, with the longer-term line at ~$95.50. These are important levels to watch. A breach of the upper resistance line would suggest a re-test of the previous highs near $99, with potential for a test of it's all-time high of $100.44.

GLD US Gold ETF

Source: Stockcharts

Meanwhile, credit spreads seem impervious to the macro fragility implied by the charts above. CDS spreads in Europe and the U.S. continue to consolidate near their intermediate-term lows.

US and European CDS Indices

In conclusion, several important macro indicators are testing important resistance and support levels, but the pennant-shaped consolidation patterns suggest trend-continuation at this time. As such, stock markets are likely to move sideways in the short-term, with the potential for a short-term correction driven by commodity weakness. The most likely intermediate-term direction for stocks is up, with the potential for the S&P to move as high as 1200 before we begin wave 3 down. Should 980 be taken out on the S&P, we would look for a more immediate, steeper decline to ensue.

For longer-term context, I leave you with Doug Short's most recent chart of the Three Mega Bear Markets.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)